Here's my next planned week. Slightly behind on Concepts and Environment Mock Ups, so they're a priority for now.

Thursday, March 5, 2015

EP: Research - Magrunner

I thought The Talos Principle was the closest thing in terms of game mechanics to what I anted from my game level. I also thought Dark Souls was the closest thing I wanted to the aesthetic and tone I wanted. However, I've found a game that has a nice mixture of the two; Magrunner. Magrunner seems to be a first-person puzzle cthulhu-lore inspired game.

I love the mixture of dark, Lovecraftian story mixed with a blend of The Talos Principle, Portal & Half-Life 2 gameplay. However, I do think the colour palettes and lighting is a little to varied and saturated within Magrunner. I don't think I will go quite so vibrant and eclectic with the lighting, however I do like the otherworldly mix of colours, light and architecture.

I love the mixture of dark, Lovecraftian story mixed with a blend of The Talos Principle, Portal & Half-Life 2 gameplay. However, I do think the colour palettes and lighting is a little to varied and saturated within Magrunner. I don't think I will go quite so vibrant and eclectic with the lighting, however I do like the otherworldly mix of colours, light and architecture.

|

| My 'Magrunner' Inspiration Board |

EP: Research - Half-Life 2 & Portal

Half-Life 2 & Portal have been something I have looked at later on mainly for the puzzle mechanic aspects that it has. These games by Valve often have a puzzle-based type of level progression. If it's simple or complex, there's always a sense of obstacles for players to overcome throughout the level that the player is within at that time.

I've also noticed with Half-Life 2 and Portal that there are no models for the players limbs in the First-Person view and there are no animations played for when buttons, levels and objects are interacted with. I think if I took this same approach to design of the character, it would save me having to model, rig and animate arms limbs for the player character which would save me time on the project.

|

| My 'Half-Life 2' Inspiration Board |

EP: Story Setting

I put together a concise description of the backstory and player character experience in the game level I'm creating. It's a mix of the several ideas brought together on the game lore documents I've written up. There are heavy Biblical tones and I've taken a lot of inspiration from dark theme fantasy games and books.

Sunday, March 1, 2015

EP: Technical Planning

I've laid out a list of the different kind of software I'll be using for each part of the development process. With it laid out in front of me it should give me a good feel for the kind of workflow I'll have. I'm hoping it'll also help me gauge a plan for what areas to start on first and organize the different priorities of all of the assets needed.

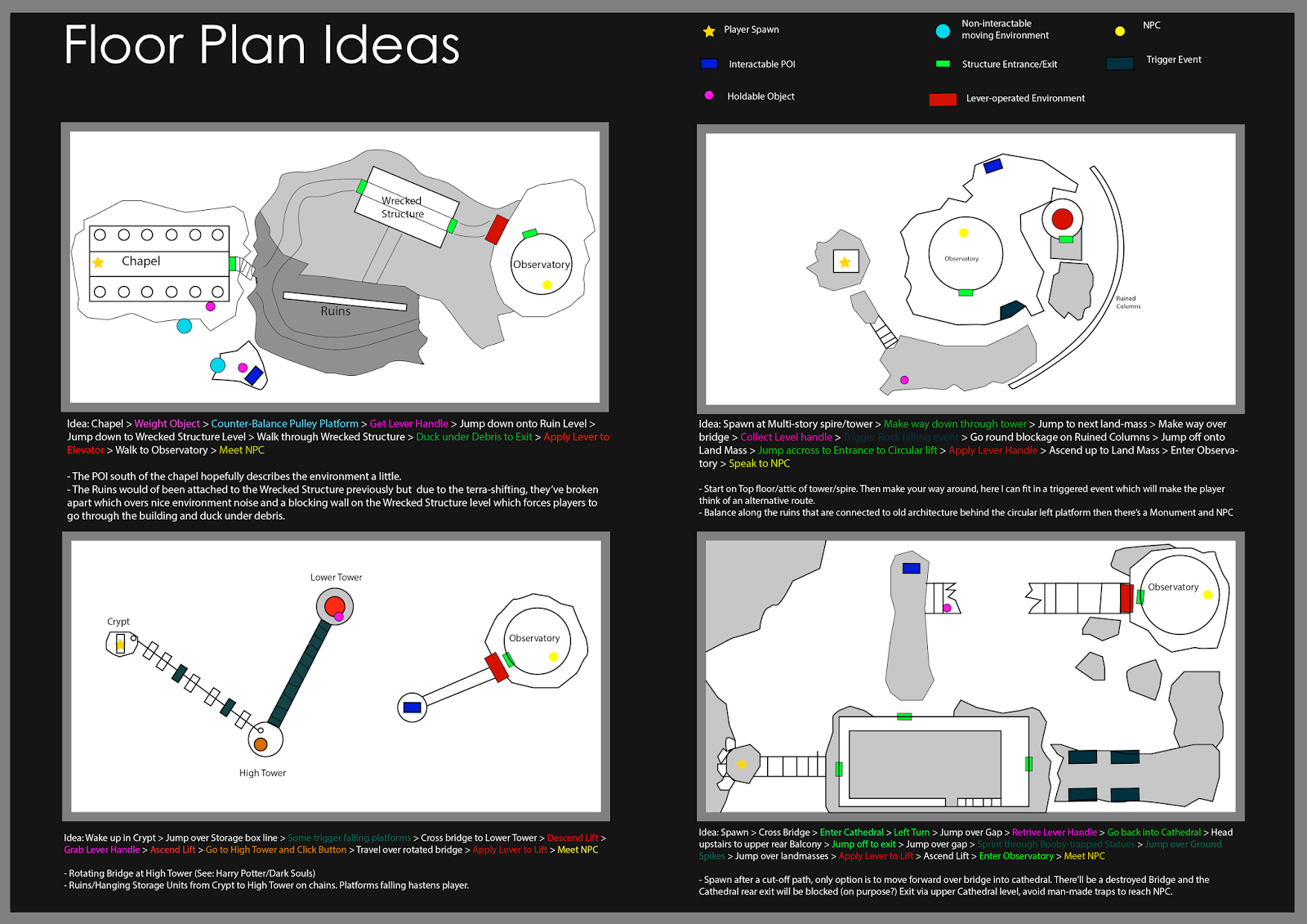

EP: Floor Plan Ideas

Here are some Floor Plan ideas I've come up with. I've been trying to implement small objectives/puzzles into the levels and also think about the location, architecture and some potential physical layouts that can tell the story of the area. I also thought up some archetypical traps and puzzle attributes to add to the environment like:

- Boulders/Falling Environment

- Ground Spikes

- Levers & Buttons

- Elevators

- Confined Spaces - Crouch Mechanic orientated

- Timed Platforms

I've tried to include a 'Monument' in each idea so I can give atleast a little non-interpretive information to the player so they can gain some inkling of where they are with assurance. I decided to go with an 'Observatory' structure for where the NPC resides. The backstory idea currently of the NPC is:

- Boulders/Falling Environment

- Ground Spikes

- Levers & Buttons

- Elevators

- Confined Spaces - Crouch Mechanic orientated

- Timed Platforms

I've tried to include a 'Monument' in each idea so I can give atleast a little non-interpretive information to the player so they can gain some inkling of where they are with assurance. I decided to go with an 'Observatory' structure for where the NPC resides. The backstory idea currently of the NPC is:

'The Watcher'

Physically huge hole in head.

Speaks about being

sent to this observatorium as a punishment.

He betrayed the

higher-up Gods (creators). Jealous of the newer creations, feels betrayed

himself because he was one of the many first-born species.

Sentenced to suffer

and watch the very creations he despises until death.

I've been mindful of keeping the curse/hex/emotion thing forming into a tangible physical attribute for him. I'm still thinking of different bios and ideas, this isn't set in stone but I'm happy with the idea of the NPC residing in an observatory locked away/stranded in a high place away from civilization.

In terms of level, I've included some Trigger events - mostly falling/decaying environment areas, meant to provide the player with a blockage in their pathway, forcing them to think of an alternative route. On top of this, it also describes the scene as being ancient, old and not looked after. I may end up merging some aspects of every floor plan together depending on feedback from peers.

|

| My Floor Plan Ideas |

EDIT AFTER FEEDBACK:

#4 Extra Platforms

at the End of the level,falling/destroyed-by-trigger environment. Force player to learn patterns.

#1 Replacement for

Weighted Cage area - Pick up objects to form pathways. E.g. Plank

#1 and #3 have a

direct view of the end of the level. Gives visual representation of a goal for

the player to aim for.

#4 Hides the end

objective but discovering the Observatory goal gives the player a sense of

exploration. Another feeling of success?

EP: Research - Build a Bad Guy Workshop

Found this article on Gamasutra which goes into some of the different attributes various enemies have in games (Link). The article explains that level design often makes or breaks a game and enemies (which from reading Koster, can be identified as an 'obstacle') are great way to make a level interesting and a good way to deliver challenges/puzzles to the player.

While I don't think my level will feature any enemies, I think I can use some of the attributes that this 'Build a Bad Guy Workshop' article has identified and possibly apply them to environment obstacles. I think by using some of these attributes I can create puzzles and obstacles for the player to overcome which will hopefully make my level more interesting and 'game-like'. I've put together a list of some of the attributes I think I may be able to apply, or interesting concepts I think I might be able to make work.

While I don't think my level will feature any enemies, I think I can use some of the attributes that this 'Build a Bad Guy Workshop' article has identified and possibly apply them to environment obstacles. I think by using some of these attributes I can create puzzles and obstacles for the player to overcome which will hopefully make my level more interesting and 'game-like'. I've put together a list of some of the attributes I think I may be able to apply, or interesting concepts I think I might be able to make work.

EP: Research - Dark Souls Developer Interview

Dark Souls Interview held by Kadoman Otsuka in 'Dark Souls: Design Works'

Featuring:

- Hidetaka Miyazaki

- Daisuke Satake

- Hiroshi Nakamura

- Masamori Waragai

- Mai Hatsuyama

"KADOMAN OTSUKA (HEREINAFTER OTSUKA):

I'd like to start this interview by asking Miyazaki about the process of ordering designs.

MIYAZAKI: The design ordering process for "Dark Souls" can be divided into two main categories. The first involves providing the designers with simple keywords we brainstormed during the early stages of project development and allowing them to design freely. We take the images they produce and provide feedback, make adjustments as necessary, or incorporate their ideas into our plans. Characters like Gaping Dragon, Egg Burdened, and Gravelord Nito came out of this process. The second process comes into play once we've settled on the basic details of the game world. At that point we are able to make more detailed design requests. These requests usually include information like how the design will be used, where in the game the design will be used, and the specific purpose of the design in terms of what it will represent in the game. In this case, I generally have a pretty good idea of what I want. Characters like Mimic and Gargoyle were created through this process. Either way, I am the one who hands out the orders and I work directly with each designer instead of having a middleman between us."

I find it really interesting that a lot of the concept generation took place from Miyazaki feeding the designers a few keywords and leaving the rest up to them. Design with such a small amount of restrictions can be overwhelming and aimless but I suppose if the little information that is given is informative and inspiring, a lot can come from it.

"OTSUKA: Did you have any concerns that giving your designers too much freedom would result in a lack of unity in the game art?

MIYAZAKI: It's true that a game's art work needs a certain level of solidarity, but I still decided to give our designers as much freedom as possible. As the one who makes the final call on everything, I have some unique quirks and I know the designers do too. It was my hope that these quirks would somehow work together to produce a special kind of harmony. I feel like enjoying the collaborative experience with a great team of unique designers will build a rich and intricate world. I've found that each designer has their own "in" when it comes to design work. While some designers like to approach a design from a philosophical angle, others do better when they have a character backstory to work off of. In this way, the different designers are able to bring their own touch to the project and possibly inspire new ideas in their teammates, eventually leading to a new level of depth in the final product. Having said all of that, I will add that every project requires a certain degree of direction to keep everyone on track (laughs) For "Dark Souls", I put three major guidelines in place: Gods and knights centered around Anor Londo, demonic chaos and flames centered around Lost Izalith, and the theme of death centered around Gravelord Nito. To these themes we added the special concept of ancient dragons that predate all life, and this formed the basis for "Dark Souls". The rest was left to the somewhat "free design" philosophy I described earlier. Another possibly surprising tactic that we used was to have every designer involved in every aspect of the game instead of assigning individual designers to things like maps, characters and equipment."

Miyazaki shows that he tailors his way of working to the individuals he is working with at the time. Additionally, on the topic of vagueness in concept generation, I find it very insightful that Dark Souls had a lot of its lore, story and characters built around visual concepts first. Usually script would come first, or some kind of backstory with already established characters and locations to some extent.

"OTSUKA: Do your design orders tend to be more abstract in nature?

MIYAZAKI: ...I'll do my best to throw a variety of keywords into our conversations to stimulate each designer's imagination. If we were to take Nakamura as an example, I often discussed topics like philosophy and the world as a whole with him.

WARAGAI: He'll start talking about the wonders of the universe at the slightest provocation, (laughs)

MIYAZAKI: Totally, especially at the beginning. We often discussed topics like how the world began, life and death, the meaning of fire, and the position of the Four Kings relative to humans. I find these conversations inspiring, which helps to keep me from trapping myself in a creative corner."

Nakamura's philosophical approach is quite inspiring to me, I like the idea that Nakamura approaches concept design in more ways than the obvious. Giving a character/creature some pre-thought out story can help the visual style a lot.

"OTSUKA: I'd like to move on to discuss in detail the design work associated with each area of the game. Shall we start with the Northern Undead Asylum?

MIYAZAKI: It might sound counter-intuitive to work on the tutorial area last, but by pretty much finishing the rest of the game first we can go into the creation of the tutorial stage with a complete list of everything that will be vital for the player to learn at the beginning with regards to how the game works, the lore, and other information. If I recall correctly, we decided to make the Undead Asylum a place that would summarize the world of "Dark Souls" and its dark fantasy vibe. We decided to be straightforward with themes like a dank dungeon, unfeeling stonework, as well as the chilling and sorrowful flavor I mentioned earlier. "

I've never thougth of this before but now I've read this, it seems obvious. It's a great idea with perfect reasoning, to create the tutorial last as once a game is practically finished the designers are going to have a better understanding of the journey the player has to make and therefore can provide better lessons for the player to learn when introduced to the game. I also really like the fact that Miyazaki wanted to reflect the entire games tone and character in the tutorial level. it sets the tone, mood and gives the player a taster of what to expect in the rest of the game.

"OTSUKA: Okay, let's move north now to Sen's Fortress.

MIYAZAKI: As I recall, we took a lot of time just to get to the rough draft of the map, and had quite a bit of trouble fitting it into the game.

WARAGAI: It's true, we did. The "gauntlet of traps" was a fairly easy concept to figure out, with things like a pendulum, rolling boulders, and such. I just laid out a bunch of archetypical traps that players would easily be able to identify or that they would fine easy to relate to."

Very simple point but I shall take this into consideration when making my own level, just writing down various potential traps, objectives and goals for the player to overcome can help me form a better idea of how I want my level to be built.

"OTSUKA: Was the idea that he is just constantly suffering from a sense of starvation?

NAKAMURA: Pretty much, yes. That's all he thinks about and the obsession literally consumed him to the point where things like his head and other physical features degenerated severely. Now, rather than eating with his mouth, he uses his whole body to directly consume anything he perceives as food. Adopting this form was the only way he could survive. With all of his other abilities similarly dissolved, the Gaping Dragon turned into a specialized creature that only lives to devour. I think his location also contributed to his change, as he lives in a very remote place that is rare visited by other creatures like humans. As a result, he was forced to survive by eating things like nasty rotten carcasses."

I think this is exactly the type of thing I have been thinking of when keeping the design of my NPC Guide in mind. I want some kind of inner emotion, intangible feeling/sacrifice/mental state to reflect in the physical nature of the NPC's design. The way Nakamura describes the The Gaping Dragon is so very in-tune with how it physically appears to the player, it's a instant visual representation of the creatures emotions - great storytelling.

"OTSUKA: Speaking of motion, the way the Attack Dogs in the Depths moved was quite unsettling.

MIYAZAKI: Technically speaking, that motion is a little off but we found the somewhat unnatural movement to have an unsettling quality to it, as you said, so we decided to leave it that way. If you make everything in a game too perfect, you lose that creepy otherworldly vibe that you can only get from something that feels more organic."

I like that Miyazaki mentions sometimes keeping imperfections in your work can make it feel more organic. This particular comment also nicely fits in with the style that I want, as aiming for that otherworldly, unsettling appearance when it comes to my NPC Guide design is my goal and clearly imperfections can help the design process well.

I'd like to start this interview by asking Miyazaki about the process of ordering designs.

MIYAZAKI: The design ordering process for "Dark Souls" can be divided into two main categories. The first involves providing the designers with simple keywords we brainstormed during the early stages of project development and allowing them to design freely. We take the images they produce and provide feedback, make adjustments as necessary, or incorporate their ideas into our plans. Characters like Gaping Dragon, Egg Burdened, and Gravelord Nito came out of this process. The second process comes into play once we've settled on the basic details of the game world. At that point we are able to make more detailed design requests. These requests usually include information like how the design will be used, where in the game the design will be used, and the specific purpose of the design in terms of what it will represent in the game. In this case, I generally have a pretty good idea of what I want. Characters like Mimic and Gargoyle were created through this process. Either way, I am the one who hands out the orders and I work directly with each designer instead of having a middleman between us."

I find it really interesting that a lot of the concept generation took place from Miyazaki feeding the designers a few keywords and leaving the rest up to them. Design with such a small amount of restrictions can be overwhelming and aimless but I suppose if the little information that is given is informative and inspiring, a lot can come from it.

"OTSUKA: Did you have any concerns that giving your designers too much freedom would result in a lack of unity in the game art?

MIYAZAKI: It's true that a game's art work needs a certain level of solidarity, but I still decided to give our designers as much freedom as possible. As the one who makes the final call on everything, I have some unique quirks and I know the designers do too. It was my hope that these quirks would somehow work together to produce a special kind of harmony. I feel like enjoying the collaborative experience with a great team of unique designers will build a rich and intricate world. I've found that each designer has their own "in" when it comes to design work. While some designers like to approach a design from a philosophical angle, others do better when they have a character backstory to work off of. In this way, the different designers are able to bring their own touch to the project and possibly inspire new ideas in their teammates, eventually leading to a new level of depth in the final product. Having said all of that, I will add that every project requires a certain degree of direction to keep everyone on track (laughs) For "Dark Souls", I put three major guidelines in place: Gods and knights centered around Anor Londo, demonic chaos and flames centered around Lost Izalith, and the theme of death centered around Gravelord Nito. To these themes we added the special concept of ancient dragons that predate all life, and this formed the basis for "Dark Souls". The rest was left to the somewhat "free design" philosophy I described earlier. Another possibly surprising tactic that we used was to have every designer involved in every aspect of the game instead of assigning individual designers to things like maps, characters and equipment."

Miyazaki shows that he tailors his way of working to the individuals he is working with at the time. Additionally, on the topic of vagueness in concept generation, I find it very insightful that Dark Souls had a lot of its lore, story and characters built around visual concepts first. Usually script would come first, or some kind of backstory with already established characters and locations to some extent.

"OTSUKA: Do your design orders tend to be more abstract in nature?

MIYAZAKI: ...I'll do my best to throw a variety of keywords into our conversations to stimulate each designer's imagination. If we were to take Nakamura as an example, I often discussed topics like philosophy and the world as a whole with him.

WARAGAI: He'll start talking about the wonders of the universe at the slightest provocation, (laughs)

MIYAZAKI: Totally, especially at the beginning. We often discussed topics like how the world began, life and death, the meaning of fire, and the position of the Four Kings relative to humans. I find these conversations inspiring, which helps to keep me from trapping myself in a creative corner."

Nakamura's philosophical approach is quite inspiring to me, I like the idea that Nakamura approaches concept design in more ways than the obvious. Giving a character/creature some pre-thought out story can help the visual style a lot.

"OTSUKA: I'd like to move on to discuss in detail the design work associated with each area of the game. Shall we start with the Northern Undead Asylum?

MIYAZAKI: It might sound counter-intuitive to work on the tutorial area last, but by pretty much finishing the rest of the game first we can go into the creation of the tutorial stage with a complete list of everything that will be vital for the player to learn at the beginning with regards to how the game works, the lore, and other information. If I recall correctly, we decided to make the Undead Asylum a place that would summarize the world of "Dark Souls" and its dark fantasy vibe. We decided to be straightforward with themes like a dank dungeon, unfeeling stonework, as well as the chilling and sorrowful flavor I mentioned earlier. "

I've never thougth of this before but now I've read this, it seems obvious. It's a great idea with perfect reasoning, to create the tutorial last as once a game is practically finished the designers are going to have a better understanding of the journey the player has to make and therefore can provide better lessons for the player to learn when introduced to the game. I also really like the fact that Miyazaki wanted to reflect the entire games tone and character in the tutorial level. it sets the tone, mood and gives the player a taster of what to expect in the rest of the game.

"OTSUKA: Okay, let's move north now to Sen's Fortress.

MIYAZAKI: As I recall, we took a lot of time just to get to the rough draft of the map, and had quite a bit of trouble fitting it into the game.

WARAGAI: It's true, we did. The "gauntlet of traps" was a fairly easy concept to figure out, with things like a pendulum, rolling boulders, and such. I just laid out a bunch of archetypical traps that players would easily be able to identify or that they would fine easy to relate to."

Very simple point but I shall take this into consideration when making my own level, just writing down various potential traps, objectives and goals for the player to overcome can help me form a better idea of how I want my level to be built.

"OTSUKA: Was the idea that he is just constantly suffering from a sense of starvation?

NAKAMURA: Pretty much, yes. That's all he thinks about and the obsession literally consumed him to the point where things like his head and other physical features degenerated severely. Now, rather than eating with his mouth, he uses his whole body to directly consume anything he perceives as food. Adopting this form was the only way he could survive. With all of his other abilities similarly dissolved, the Gaping Dragon turned into a specialized creature that only lives to devour. I think his location also contributed to his change, as he lives in a very remote place that is rare visited by other creatures like humans. As a result, he was forced to survive by eating things like nasty rotten carcasses."

I think this is exactly the type of thing I have been thinking of when keeping the design of my NPC Guide in mind. I want some kind of inner emotion, intangible feeling/sacrifice/mental state to reflect in the physical nature of the NPC's design. The way Nakamura describes the The Gaping Dragon is so very in-tune with how it physically appears to the player, it's a instant visual representation of the creatures emotions - great storytelling.

"OTSUKA: Speaking of motion, the way the Attack Dogs in the Depths moved was quite unsettling.

MIYAZAKI: Technically speaking, that motion is a little off but we found the somewhat unnatural movement to have an unsettling quality to it, as you said, so we decided to leave it that way. If you make everything in a game too perfect, you lose that creepy otherworldly vibe that you can only get from something that feels more organic."

I like that Miyazaki mentions sometimes keeping imperfections in your work can make it feel more organic. This particular comment also nicely fits in with the style that I want, as aiming for that otherworldly, unsettling appearance when it comes to my NPC Guide design is my goal and clearly imperfections can help the design process well.

EP: Research - A Theory of Fun by Raph Koster

I've been reading 'A Theory of Fun' by Raph Koster in order to gain a deeper understanding of why people play games, what it is that they enjoy and how I can use this understanding to inform my own choices when it comes to designing my game.

"Based on my reading, the human brain is mostly a voracious consumer of patterns, a soft pudgy gray Pac-Man of concepts. Games are just exceptionally tasty patterns to eat up.

When you watch a kid learn, you see there's a recognizable pattern to what they do. They give it a try once -- it seems that a kid can't learn by being taught. They have to make mistakes themselves. They push at boundaries to test them and see how far they will bend. They watch the same video over and over and over and over and over..."

Koster's commentary on how children learn through trial and error is really interesting. I think he's right when he says that children appear to have an easier time in doing something themselves, potentially failing and then learning from repeated tries. Rather than just giving instruction, the act of being practical about a task or challenge may be seen as much more effective in giving a child new information that sticks and is understood.

I think I should bare this in mind in Game Design as, even if the target audience of a game may not be aimed at a younger mind, I'd argue that we still hold that basic 'rule' of, we want to try to find a solution to a problem; if something fails we can use that information to inform our next attempt. This is already in games, mechanics like respawning help this type of learning. The majority of the time, after dying in a game you respawn and are presented with another opportunity to try again.

"Simply put, the brain is made to fill in blanks. We do this so much we don't even realize we're doing it....

We've learned that if you show someone a movie with a lot of jugglers in it an tell them in advance to count the jugglers, they will probably miss the large pink gorilla in the background, even though it's a somewhat noticeable object. The brain is good at cutting out the irrelevant."

I think Koster's point about how peoples brains work on 'autopilot' a lot of the time and fill in the blanks for us is a great observation. I think this is useful information to keep in mind when designing a game.

For example, say I were to design a 3D game environment as part of a game level, it's efficient to have the least amount of poly's and high-res textures as possible so the game can run smoother and be as optimized as possible. Taking the brain's autopilot qualities into account when the player is in said environment, it means that I can concentrate all the detail into 'Hero Objects' -- the most noticeable assets in the environment that the player will be more inclined to notice. Which then allows me to have the less important assets of the environment to be of a lower resolution because it's just there to fill the blanks of the image that the brain has and it won't be consciously focused on by the player.

This form of design, using Hero Objects to draw in the player at higher levels of detail, is used in most games today. It's proven to be effective as it has become a part of most (if not, all) 3D based games. I understand why it's used and why it's effective in what it does. This is also a relief in the production process as it means not every asset, not every model and/or texture has to be of the highest quality.

A little more on this....

"When we grasp a pattern, we usually get bored with it and iconify it...

One might argue that the essence of much of art is forcing us to see things as they are rather than as we assume them to be -- poems about trees that force us to look at the majesty of bark and the subtlety of leaf, the strength of trunk and the amazing abstractness of the negative space between boughs -- those are getting us to ignore the image in our head of "wood, big greenish whatever" that we take for granted."

I like the imagery Koster uses to illustrate his point, brilliant stuff. Really though, I can see what he means, we like to simplify things in our heads, iconify things that we don't want to pay attention to. I think that Game luckily allows for this as it may now be normal to expect characters in a game to be hyper-realistic but in order to have foliage, for example, in a game to be as visually in-depth and descriptive as the image Koster has painted would be a bad idea as it would make the requirements to run the game incredibly high and unrealistic. Taking advantage of these psychological tropes of people seems to have informed how games are made in a huge way. You may get players that stop, take a look around and realise not everything looks as good up close as it does from a far but it's a necessity in game design. Also, gamers understand this, in a much less long-winded way but it is definitely understood by players as just a 'thing that happens in games' -- it comes with the platform, the medium.

"Grok is a really useful word. Robert Heinlein coined it in his novel Stranger in a Strange Land. It means that you understand something so thoroughly that you have become one with it and even love it. It's a profound understanding beyond intuition or empathy..."

Koster then goes on to talk about his experience with guitars and that for his birthday his Wife bought him a Mandolin and despite them quite different from one another, he was able to apply his experience with guitars to playing the Mandolin.

"I have grokked enough about stringed instruments to create a library of chunked knowledge to apply. When I was playing the guitar all those years, I was also working on more obscure stuff, deepening my knowledge of the intervals between notes, mastering rhythm, understanding harmonic progression."

I love that Koster mentions this 'mental library' that we create from learning things that we then go on to apply to other things that relate in some way (or maybe not at all). This sounds a lot like the 'mental inventory' that I have heard RagnarRox on YouTube speak about -- only the 'mental inventory' is more aimed towards just games. The idea that we take previous information learned and practice we've done and apply it to new experiences is very apparent in gamers. For instance, while games are pretty much required to have some kind of guide or tutorial, most people with previous experience in games will already have assumed most of the information given in a games tutorials. Controls, the meanings of colours, menu systems, general mechanics are all things that gamers may be able to adapt to instantly with no need of telling what to do because they've already built up a 'mental inventory' of how games 'usually' work and what is expected.

When you have the information that players will take some things for granted in your game, it can allow you to throw a curveball in there and do something unexpected, pattern-breaking and 'new' to make a game more interesting. Everyone loves a twist, right?

Antichamber, for example, is a game that is based entirely on combating pre-established assumptions on how the game is going to work. Because of that, the designers of the game have said that gamers have a harder time completing it than people who have little to no experience with first-person games because they make less assumptions and think outside of a game mentality.

"Human beings are all about progress. We like life to be easier. We're lazy that way. We like to find ways to avoid work. We like to find ways to keep from doing something over and over. We dislike tedium, sure, but the fact is that we crave predictability."

"And since we dislike tedium, we'll allow unpredictability, but only inside the confines of predictable boxes, like games or TV shows. Unpredictability means new patterns to learn, therefore unpredictability is fun."

These conflicting views of what people crave is really interesting as I can see both sides of the argument and I feel I can agree with this wholeheartedly when it comes to games. In games like Portal, I recognize that I want to learn the mechanics of the level I'm on as quickly as possible so I can progress and sometimes once I've figured out a mechanics I want more of a similar task to complete that confirms the lessons I've learned. Portal does this as when you learn a new mechanic or way of puzzle-solving, it will feature that in its level design 2 or 3 times before adding a new pattern to learn. There's a constant revision and building of puzzle-solving skills that are given to the player to understand and apply.

"Successful games tend to incorporate the following elements:

I find this list of game-making elements to be really insightful, a lot of it is obvious but when you see all of the aspects of what makes games appealing to a player it's really helpful. It's also quite surprising to me that so much thought goes into the psychology of any game, even games as straightforward as checkers.

"There are also some features that should be present to make the experience a learning experience:

I think the reminder that feedback is important for the player is a great point. Playing a game, to me, is almost like a back & forth between the player and the game itself (or player & opponent). Rewards, punishments and the carrot-on-a-stick properties that are often seen in games are tools that are effectively used to teach, condition and engage players to find fun in the challenge and a want to continue/learn more.

From reading Koster's 'A Theory of Fun' I feel I've gained an understanding on why certain decisions and design choices are made within game development. There are common elements to every game that are what make the experience of games unique and appealing. The psychology of a gamers mind really matters when creating an engaging experience. It also helps with efficiency in regards to design choices that help developers focus on different areas of priority in terms of visual detail & attention.

- Trial & Error. Staying practical is a great way to engage & teach the player.

- Take advantage of player Psychology. On the technical side, use brains autopilot as an excuse to use Hero Objects and differences in asset quality to build games efficiently with minimum impact on the players experience.

- Mental Library & Assumptions. Keep in mind gamers pre-existing assumptions on how games may work.

- Manipulate predictability & unpredictability of lessons for the player in order to create variations of an experience; teaching, revision & skill development.

Raph Koster is known for being one of the lead designers on Ultima Online. He's a legend in the gaming sphere and he has a lot of experience within the industry.

"Based on my reading, the human brain is mostly a voracious consumer of patterns, a soft pudgy gray Pac-Man of concepts. Games are just exceptionally tasty patterns to eat up.

When you watch a kid learn, you see there's a recognizable pattern to what they do. They give it a try once -- it seems that a kid can't learn by being taught. They have to make mistakes themselves. They push at boundaries to test them and see how far they will bend. They watch the same video over and over and over and over and over..."

Koster's commentary on how children learn through trial and error is really interesting. I think he's right when he says that children appear to have an easier time in doing something themselves, potentially failing and then learning from repeated tries. Rather than just giving instruction, the act of being practical about a task or challenge may be seen as much more effective in giving a child new information that sticks and is understood.

I think I should bare this in mind in Game Design as, even if the target audience of a game may not be aimed at a younger mind, I'd argue that we still hold that basic 'rule' of, we want to try to find a solution to a problem; if something fails we can use that information to inform our next attempt. This is already in games, mechanics like respawning help this type of learning. The majority of the time, after dying in a game you respawn and are presented with another opportunity to try again.

"Simply put, the brain is made to fill in blanks. We do this so much we don't even realize we're doing it....

We've learned that if you show someone a movie with a lot of jugglers in it an tell them in advance to count the jugglers, they will probably miss the large pink gorilla in the background, even though it's a somewhat noticeable object. The brain is good at cutting out the irrelevant."

I think Koster's point about how peoples brains work on 'autopilot' a lot of the time and fill in the blanks for us is a great observation. I think this is useful information to keep in mind when designing a game.

For example, say I were to design a 3D game environment as part of a game level, it's efficient to have the least amount of poly's and high-res textures as possible so the game can run smoother and be as optimized as possible. Taking the brain's autopilot qualities into account when the player is in said environment, it means that I can concentrate all the detail into 'Hero Objects' -- the most noticeable assets in the environment that the player will be more inclined to notice. Which then allows me to have the less important assets of the environment to be of a lower resolution because it's just there to fill the blanks of the image that the brain has and it won't be consciously focused on by the player.

This form of design, using Hero Objects to draw in the player at higher levels of detail, is used in most games today. It's proven to be effective as it has become a part of most (if not, all) 3D based games. I understand why it's used and why it's effective in what it does. This is also a relief in the production process as it means not every asset, not every model and/or texture has to be of the highest quality.

A little more on this....

"When we grasp a pattern, we usually get bored with it and iconify it...

One might argue that the essence of much of art is forcing us to see things as they are rather than as we assume them to be -- poems about trees that force us to look at the majesty of bark and the subtlety of leaf, the strength of trunk and the amazing abstractness of the negative space between boughs -- those are getting us to ignore the image in our head of "wood, big greenish whatever" that we take for granted."

I like the imagery Koster uses to illustrate his point, brilliant stuff. Really though, I can see what he means, we like to simplify things in our heads, iconify things that we don't want to pay attention to. I think that Game luckily allows for this as it may now be normal to expect characters in a game to be hyper-realistic but in order to have foliage, for example, in a game to be as visually in-depth and descriptive as the image Koster has painted would be a bad idea as it would make the requirements to run the game incredibly high and unrealistic. Taking advantage of these psychological tropes of people seems to have informed how games are made in a huge way. You may get players that stop, take a look around and realise not everything looks as good up close as it does from a far but it's a necessity in game design. Also, gamers understand this, in a much less long-winded way but it is definitely understood by players as just a 'thing that happens in games' -- it comes with the platform, the medium.

"Grok is a really useful word. Robert Heinlein coined it in his novel Stranger in a Strange Land. It means that you understand something so thoroughly that you have become one with it and even love it. It's a profound understanding beyond intuition or empathy..."

Koster then goes on to talk about his experience with guitars and that for his birthday his Wife bought him a Mandolin and despite them quite different from one another, he was able to apply his experience with guitars to playing the Mandolin.

"I have grokked enough about stringed instruments to create a library of chunked knowledge to apply. When I was playing the guitar all those years, I was also working on more obscure stuff, deepening my knowledge of the intervals between notes, mastering rhythm, understanding harmonic progression."

I love that Koster mentions this 'mental library' that we create from learning things that we then go on to apply to other things that relate in some way (or maybe not at all). This sounds a lot like the 'mental inventory' that I have heard RagnarRox on YouTube speak about -- only the 'mental inventory' is more aimed towards just games. The idea that we take previous information learned and practice we've done and apply it to new experiences is very apparent in gamers. For instance, while games are pretty much required to have some kind of guide or tutorial, most people with previous experience in games will already have assumed most of the information given in a games tutorials. Controls, the meanings of colours, menu systems, general mechanics are all things that gamers may be able to adapt to instantly with no need of telling what to do because they've already built up a 'mental inventory' of how games 'usually' work and what is expected.

When you have the information that players will take some things for granted in your game, it can allow you to throw a curveball in there and do something unexpected, pattern-breaking and 'new' to make a game more interesting. Everyone loves a twist, right?

Antichamber, for example, is a game that is based entirely on combating pre-established assumptions on how the game is going to work. Because of that, the designers of the game have said that gamers have a harder time completing it than people who have little to no experience with first-person games because they make less assumptions and think outside of a game mentality.

"Human beings are all about progress. We like life to be easier. We're lazy that way. We like to find ways to avoid work. We like to find ways to keep from doing something over and over. We dislike tedium, sure, but the fact is that we crave predictability."

"And since we dislike tedium, we'll allow unpredictability, but only inside the confines of predictable boxes, like games or TV shows. Unpredictability means new patterns to learn, therefore unpredictability is fun."

These conflicting views of what people crave is really interesting as I can see both sides of the argument and I feel I can agree with this wholeheartedly when it comes to games. In games like Portal, I recognize that I want to learn the mechanics of the level I'm on as quickly as possible so I can progress and sometimes once I've figured out a mechanics I want more of a similar task to complete that confirms the lessons I've learned. Portal does this as when you learn a new mechanic or way of puzzle-solving, it will feature that in its level design 2 or 3 times before adding a new pattern to learn. There's a constant revision and building of puzzle-solving skills that are given to the player to understand and apply.

"Successful games tend to incorporate the following elements:

- Preparation. Before taking on a given challenge, the player gets to make some choices that affect their odds of success. This might be healing up before a battle, handicapping the opponent, or practicing in advance. You might set up a strategic landscape, such as building a particular hand of cards in a card game. Prior moves in a game are automatically part of the preparation stage because all games consist of multiple challenges in a sequence.

- A sense of space. The space might be the landscape of a war game, a chess board, the network of relationships between the players during the bridge game.

- A solid core mechanic. This is a puzzle to solve, intrinsically interesting rule set into which content can be poured. An example might be "moving a piece of chess." The core mechanic is usually a fairly small rule; the intricacies of games come from either having a lot of mechanics or having a few, very elegantly chosen ones.

- A range of challenges. This is basically content. It does not change the rules, it operates within the rules and brings slightly different parameters to the table. Each enemy you might encounter in a game is one of these.

- A range of abilities required to solve the encounter. If all you have is a hammer and you can only do one thing with it, then the game is going to be dull. This is a test that tic-tac-toe fails but that checkers meets; in a game of checkers you start learning the importance of forcing the other player into a disadvantageous jump. Most games unfold abilities over time, until at a high levels you have many possible stratagems to choose from.

- Skill required in using the abilities. Bad choices lead to failure in the encounter. This skill can of any sort, really: resource management during the encounter, failures in timing, in physical dexterity, and failures to monitor all the variables that are in motion."

I find this list of game-making elements to be really insightful, a lot of it is obvious but when you see all of the aspects of what makes games appealing to a player it's really helpful. It's also quite surprising to me that so much thought goes into the psychology of any game, even games as straightforward as checkers.

"There are also some features that should be present to make the experience a learning experience:

- A variable feedback system. The result of the encounter should not be completely predictable. Ideally, greater skill in completing the challenge should lead to better rewards. In a game like chess, the variable feedback is your opponent's response to your move.

- The Mastery Problem must be dealt with. High-level players can't get big benefits from easy encounters or they will bottom-feed. Inexpert players will be unable to get the most out of the game.

- Failure must have a cost. At the very least there is an opportunity cost, and there may be more. Next time you attempt the challenge, you are assumed to come into it from scratch--there are no--"do-overs." Next time you try, you may be prepared differently."

I think the reminder that feedback is important for the player is a great point. Playing a game, to me, is almost like a back & forth between the player and the game itself (or player & opponent). Rewards, punishments and the carrot-on-a-stick properties that are often seen in games are tools that are effectively used to teach, condition and engage players to find fun in the challenge and a want to continue/learn more.

From reading Koster's 'A Theory of Fun' I feel I've gained an understanding on why certain decisions and design choices are made within game development. There are common elements to every game that are what make the experience of games unique and appealing. The psychology of a gamers mind really matters when creating an engaging experience. It also helps with efficiency in regards to design choices that help developers focus on different areas of priority in terms of visual detail & attention.

- Trial & Error. Staying practical is a great way to engage & teach the player.

- Take advantage of player Psychology. On the technical side, use brains autopilot as an excuse to use Hero Objects and differences in asset quality to build games efficiently with minimum impact on the players experience.

- Mental Library & Assumptions. Keep in mind gamers pre-existing assumptions on how games may work.

- Manipulate predictability & unpredictability of lessons for the player in order to create variations of an experience; teaching, revision & skill development.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)